A well-known Brazilian agent told me about the futuristic Flyzoo Hotel soon after it opened in 2019. As it turned out, I was unable to visit this 290 Room 4-star hotel packed with the latest hotel technology until a month ago, after Covid had passed. I had ventured to Hangzhou, the hometown of Jack Ma, the business genius who in the late nineties launched Alibaba, now a golgothan Chinese B2B company that helps many importers around the world connect with exporting Chinese factories. For most people that would be achievement enough, but this legendary titan went on to found Taobao and Tmall, the Chinese equivalent of Amazon, and as part of that developed Alipay, one of China’s two national payment systems, from which he then ventured into the financial and credit services in the form of Ant Financial and then into cloud services. The Flyzoo Hotel, developed by his e-commerce company, Alibaba, and located within its business campus on the outskirts of Hangzhou, incorporates the latest in digital technology. Given his track record in disrupting industries, this was surely worth a visit.

Before I describe the Flyzoo Hotel, let’s first put it into its proper context. As a leading luxury tour company, Imperial Tours typically accommodates its guests at the finest hotels in China, themselves often amongst the finest in the world. Typically, these are full-service hotels with multiple restaurants and bars, less than 200 rooms and a high staff to guest ratio. Given that most leading properties in China are relatively new and spacious, what distinguishes the crème de la crème is the quality of their highly personalized service, and you can’t get great service without amazing staff, fabulous IT, efficient management and subsequently high room rates. This is not the basis on which the Flyzoo Hotel should be judged. This property by contrast seeks to excel in functionality rather than in service. It aims to feed and accommodate its guests in comfortable 4-star circumstances efficiently. That is its purpose and how it should be judged – against a Holiday Inn rather than the Four Seasons.

Chinese domestic travelers begin to interact with the Flyzoo Hotel by booking a room on the Alibaba travel app, Fliggy. This allows them to specify both the floor and view in the chosen room category for their stay. They subsequently use this app again to check in to the hotel on their day of arrival – scanning their ID Card and taking a digital photograph of their faces. This image will be incorporated into the hotel database’s facial recognition software. As a result, when they enter the hotel elevator, their floor will automatically be selected. Their room door lock is equipped with the same software. A camera mounted on the door recognizes and admits them to the room automatically. Sadly, foreigners cannot use the app in the same way yet; overseas visitors must scan their passports and take a facial photo at a booth in the lobby as part of their check-in process. Although there is a bell boy in the lobby to help with bags and also a Front Desk manager loitering in the background, these don’t really have much to contribute in the check in process.

The most useful service-provider in the hotel lobby is in fact a mobile robotic concierge. As this pleasant-looking and sounding Chinese-speaking appliance glides its way towards you, a list of informational menu options lights up on its welcoming screen to be selected. Amongst other options, you can ask it to introduce you to the hotel, for directions to the restaurant, or to explain the check-out procedures.

Exhausted by my exertions with the robotic dancing queen, I made my way to the room. As you can see in these images, this is comfortably, efficiently and functionally furnished in keeping with expectations for a four-star property. Though there are mounted wall switches to control the lights, temperature and curtains, each room is equipped with a Chinese-speaking virtual assistant, the equivalent of Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa. This can be commanded in Chinese to adjust the room environment along with the TV set and music system. Additionally, if you require anything delivered to the room, from a bottle of water to a particular type of pillow or a room menu item, the virtual assistant will organize for a robot to supply this.

Humans and robots work in tandem in the dining areas. Chefs labor in the dining room’s western and Chinese cooking stations. Meanwhile, QR codes on the table tops direct diners to online restaurant menus and meal ordering programs. Shortly after inputting a table order, dishes are delivered by robots to the table. Diners have to be prompt in removing the food from the drawer at the top of the robot.

Where humans are most in evidence both in the bedrooms and in the dining rooms is in cleaning things away. Neither housekeepers’ nor busboys’ functions have yet been automated. It is an ironic comment on the future of hotel employment that the positions with the lowest paying salaries seem to be safest from being automated.

Whilst the claim will be made that a highly automated hotel makes for a soulless experience, travelers who travel at the 3 and 4 star level are value rather than service-driven. I am not expecting a remarkable service experience when I book an overnight stay at the Holiday Inn, for example. My exchanges with staff will be prompt, utilitarian and efficient. A booking in this segment focuses on value as comprised of a number of factors including price, cleanliness, comfort and convenience. The labor savings that the application of inexpensive technology and robots can provide definitely confer competitive advantage, and the Flyzoo hotel rooms seem like a great deal for the price. While some technologies such as facial recognition software and virtual assistants are bound to be incorporated into the finest hotels, I am not expecting a robotic concierge, even an all-dancing one, to replace the Peninsula concierge or the St. Regis butler anytime soon.

Daily life in China has become so reliant on using smart phone apps that I now wonder if I could survive without them! The obvious immediate obstacle for a tourist is flagging down taxis as these exclusively respond to ride-hailing apps now. That said, even though local Chinese people are using their smart phones to handle all their daily tasks from paying their phone bill, to ordering cinema tickets to renting a bike, it is NOW possible for tourists not only to get about, but also to take advantage of Chinese super-apps to facilitate their travel in China. Find out how you should best prepare for a trip to China (as of summer 2023).

Getting a Good VPN.

Any article about digital China for a westerner begins with the absolute necessity of downloading a high quality VPN. Many of the west’s favourite apps, such as Google, Gmail, Facebook, Instagram, Whatsapp, Google Maps and Google Translate are not accessible from China without one. A VPN creates a way for you to tunnel digitally through China’s Great Firewall and access these much-loved apps that are banned in China. My experience is that China’s Great Firewall has different levels of control. During a People’s Congress when Beijing is locked down tight, even the best VPN’s do not work. However, at normal times, the Great Firewall is porous. I’m not going to recommend a particular VPN in this article, but if you are thinking to use a free or a low-cost VPN, bear in mind that you generally get what you pay for. And if you arrive in China with a VPN that is ineffective, your challenge will be to download a high-quality VPN from inside China, which is that much harder (though still doable). (Android phone users should also remember that Google Play cannot be used from inside China, so if they do not have a VPN installed, they are not going to be able to install a new VPN service in China, unless they find a wifi service which already has it.) My final suggestion in this regard is in fact to download two high quality VPNs prior to your trip to China, so that if one does not work, you can try to use the other.

How to pay with an APP

Two super-apps take up the lion’s share of Chinese users’ attention, similar to how Google and Facebook divide the western digital universe between them. In China, these are Wechat and Alipay, the former established by a company called Tencent and the latter created by Jack Ma, the iconic Chinese entrepreneur behind Alibaba. The most significant feature of both is that they have established themselves for mobile payment services covering payments as wide-ranging as to the taxi driver, utility companies and for cinema bookings. Both buttress this payment service with a panoply of mini-apps supplying everything from food delivery to insurance to translation. Theis wide range of services has led to them being known as super-apps. The idea is that they are a digital one-stop shop. We don’t yet have anything like it in the west – it would be like trying to use Amazon or Apple for all our digital needs.

Until now, overseas travelers to China have experienced real problems using anything but cash to pay for goods and services in China as only a limited number of retailers accept overseas credit cards. Although it is illegal in China for retailers to refuse cash as payment, the practical reality where almost no one is using it means that outlets are increasingly unprepared to accommodate it. The great news is that now if they have either a Mastercard or a Visa credit or debit card international travelers can register and use these with the English language versions of Alipay and Wechat. After doing so, not only can overseas travelers use Alipay and Wechat to pay for services in China, but they will also benefit from the various English language mini-apps offered on either app. Alipay was the first to announce their tie-up with Mastercard in June 2023 and instructions for how to link your Mastercard to Alipay can be found here.

Wechat announced at the end of this same month, June 2023, that they will allow overseas visitors to register their international Visa, Mastercard, JCB and Discover cards in their app from August 2023. Details for how to go about doing this can be found here. (Wechat previously had a facility to allow registration of overseas credit cards on their app, but this did not always translate into being able to make payments at many retail outlets in China.)

Please note that for both Wechat and Alipay that after travelers sign up for accounts in their home countries, they will be asked to re-enter passport information and take a selfie after they have arrived in China. This is a second stage in the sign-up process that was in effect in November 2024.

English Language Alipay Services

The scan function on the top left of the home page will enable you to pay for services, provided that your Mastercard is linked to the Alipay account. The transport icon facilitates for you to get about on the bus, by metro, hail a cab as well as buy train and plane tickets. In the “How—to” icon you can use the online translation service, where an image of Chinese text will be instantly converted into English for you. This could be useful in ordering food at a restaurant or trying to work out the destination of trains and planes at stations and airports.

English Langage Wechat Services

To use Wechat to pay for stuff, press the encircled + icon in the top right corner and select “Money” to allow others to scan you, or “Scan” for you to scan others’ payment codes, depending on the situation and payment format. In addition to payment, Wechat is known for its messaging service – it is in effect the Chinese version of Whatsapp with Wechat probably more widespread in China than Whatsapp is in the west. You are safe to assume that everyone you meet in China will have a Wechat account and so if you want to stay in touch and communicate with Chinese people this is the best possible way. (You will also probably find that many of your overseas Chinese friends back home already have a Wechat account.) To get someone’s contact, click the encircled + icon in the top right hand corner and click on “Add Contacts”, then either scan their QR code or select “My Weixin ID” to allow them to scan your code. (Wechat in Chinese is called weixin.)

Translation

As you can only use Google Translate inside China with a VPN, another excellent translation app for you to consider downloading prior to travel here is DeepL. You paste text into the window and can choose to translate it quickly and accurately into any number of languages.

Navigation

If you are an Iphone user, then Apple Maps will work for you in China in English, and this is your best bet. Note that Google Maps does not work in China even with a VPN. The Map function on the Bing.com website will be all in Chinese. Similarly, popular local Chinese navigation apps like Baidu and Gaode are all in Chinese without English functionality. The only remaining option for Android users seems to be downloading an English language map from Map.Me. These are maps that you download onto your phone offline for use in China. They are available for China at a provincial or in more detail at a city level. These were useful in getting me between well-known destinations, such as a large hotel to a well-known tourist site, but when I tried finding a particular noodle store, this was not included in the map database. Therefore, this is a solid back up for most situations, but isn’t as complete as what you’re probably used to back home.

Booking Travel E.g. Hotels, Trains and Airplanes

Trip.com is a fabulous English language engine for easily and efficiently booking hotels, train tickets and airplanes in China.

Other

If you speak some Chinese, I’d also recommend you download the following apps prior to a trip to China:

– Dianping is a terrific app for restaurant reviews and bookings.

– Didi and Gaode are commonly used for ride-hailing, the latter also having a popular mapping function.

– Taobao and JD are the best for online shopping

– Ele.me and Meituan are popular for ordering food deliveries and groceries.

I hope this article has opened your eyes to the enrichment that China’s digital app universe can provide to your travels in China, as well as intimating the depth and ubiquity of apps in Chinese daily life, whether in the city or countryside. At the time of writing this article, Alipay and Wechat had only just started to accept overseas credit cards onto their platforms. The English language versions of these super-apps offer a limited range of English language mini-apps, but I’d hope that as time goes by, they will offer a wider range of traveler-friendly apps.

If you found this article helpful, please do write in with comments after your China trip on how you found and negotiated your digital travels through China and please do include what you learned so that I can update the information here. Thanks.

China invested about US$900bn from 2008 – 2023 in a national high speed rail network of over 26,000 miles (40,000km), about 13 times the length of Japan or France’s network. Like theirs, trains are designed to run at between 120 – 220mph. In 2021, during the Covid period, this mammoth infrastructural investment brought in US$104 billion in revenues, representing (according to the Paulson Institute and World Bank) a return of about 7% in lower-carbon generating interconnectivity.

Climate-conscious travelers will wish to use this network as much as possible in their journeys. Other people might wish to learn more about what travel in these trains is like and about the overall value proposition before incorporating certain train routes into their China travel.

Beijing to Xi’an – Time Comparison

For a first-time traveler to China, the obvious route to do by rail is that between Beijing and Xi’an. The fastest high-speed train between Beijing and Xi’an takes 4 hours and 11 minutes. The train arrives and departs exactly on time and the likelihood of a delay is improbable.

Travel time to West Station in Beijing is about 20 minutes from the centre of Beijing, defined as Tiananmen Square, but many travelers will be residing in Chaoyang district on Beijing’s eastern side and so can expect this journey to take 40 minutes or more. On the day of my trial, I was running late and so crossed the station and boarded the train within ten minutes. However, most people will wish to allow at least 30 minutes and tour operators may well wish to pre-book porters, as otherwise clients will be pushing their bags for long distances from their vehicle through the station and onto the train itself.

At the other end, it took me 1 hour to travel by car from Xi’an North Station to the Ritz Carlton in the south of the city. Although this is geographically considerably closer than from Xi’an airport, inner-city traffic resulted in it taking just as long. Door to door the total journey time from Beijing to Xi’an on the fastest train is therefore 6 hours and 20 minutes.

If you travel by plane, it will take you about the same transit time to go by car to T2 or T3 at Beijing International airport about 1 hour in advance. Aviation companies allow 2 hours and 15 minutes but flight time is only 1.5 hours. Assuming airport arrival 1 hour before departure and then 30 minutes at the other end to pick up your bags, then the total journey time by plane is 5.5 hours, or about 50 minutes quicker. That said, whereas train travel happens to the minute, plane travel is subject to more frequent delays.

Comparing Price, Carbon And Other Factors

The three classes of train travel in descending order are Business, First and Second. (Yes, Business is above First.) These are described in more detail in a special section below. Business is about double the price of First Class and more than triple that of Second Class. Traveling in Business by train is priced to be equivalent to the plane. By comparison “First Class” on the train, which offers much more space and comfort than Economy on the plane, is about 20% cheaper than the plane. Second class on the train, which is still slightly roomier than Economy on a plane is about half the price of the plane.

Therefore, if you are a business person prioritizing speed above all else, then traveling by plane wins. However, if the business person has some project work to do, it will be easier to complete it on the train where s/he spends more time in one place, and so it is arguable that even though the transit takes one hour longer by train, it makes for better use of time.

Climate conscious travelers will be aware that train travel results in about 14 – 16 times less emission than plane travel. Families and older travelers should be aware that the total walking distance in train stations is not dissimilar to what you encounter in airports, though the security is less bothersome.

A last consideration for the tourist is that other than skyscapes and clouds, there is little to see out of the window over the course of a plane journey. By contrast, the view from the train is fascinating, affording real insight into the huge progress that the countryside has made over the last 15 years as a result of China’s Poverty Alleviation campaign.

Which Route Makes Sense

A plane travels over 2.5 times faster than the quickest train, and we see that with a train time of 4 hours, the plane already provides a speedier transit, even if the train might overall offer a better value proposition for some people. Routes such as Beijing – Xi’an (4 hours and 11 minutes) Beijing – Shanghai (4 hours and 29 minutes) and Guilin – Hong Kong (4 hours and 7 minutes) might be considered for rail travel. A no-brainer at 1.5 hours would be Hangzhou – Huangshan. Other shorter journeys of an hour or less where the rail network should be considered are those such as Shanghai – Hangzhou, Shanghai – Suzhou or Beijing – Tianjin. I would meanwhile suggest that train routes of more than 4 hours, such as Guilin – Xi’an at about 10 hours, are not going to prove popular when a flight of 2 hours is available.

On The Train – Comparison of Business, First and Second Class

Business Class

Business class consists of 4 – 6 comfortable, electronically-adjustable, wide leather seats with an electric socket and seat table, exactly as would be found in Business on a plane.

These are contained within their own exclusive, spacious, sealed off cabins in front of the small train driver’s cabin at either tip of the train. Complimentary amenities for business class travelers include travel slippers, ear plugs, ear phones, eye mask, a vanity kit, snacks and complimentary soft drinks. There is a meal service which seems similar in quality to plane meals. Toilets, between compartments, equipped with ceramic sinks and toilet bowl, are spacious and of a cleanliness comparable to western Europe.

First Class

As seen in the photo, first class consists of two seats either side of a central aisle with a very comfortable pitch between seats. A complimentary soft drink is offered to travelers.

Second Class

As seen in the photo, second class consists of five seats separated into a 2 and 3 by a central aisle with lesser pitch between seats resulting in more rows within a rail carriage than in first class. There is however still significantly greater pitch in second class on a train than that offered in economy class on a plane. A complimentary soft drink is offered to travelers.

Process Of Getting On And Off A High Speed Train

To use a high-speed train in China, you will need to have your ID with you. For overseas travelers, this will be their passport. You will have a ticket with a hall, train number, carriage and a seat number.

China’s ticketing system has been digitized such that every booked seat is associated with an identity document and number. When you arrive in the station, you will not be able to use the turn-style ticketing barriers for local Chinese travelers because you don’t have a Chinese ID card for which these machines are built. Instead go to the side where an attendant will be waiting with a passport scanner. S/he will scan your passport to check your ID and ticket against the system.

After this ID inspection, expect to put your bags through a baggage X-ray machine. If you are in a large station with multiple waiting halls, you need to walk to your waiting hall. If you are in a smaller station, there will only be one waiting hall. When there, look for noticeboards detailing your train number and the train boarding order.

When your train is called, queue at the barrier to go onto the platform. Again, because you have a passport rather than a Chinese ID card, you will need the help of an attendant to board the train. Once you are on the platform, walk to your carriage and subsequently to your seat number. An attendant at each carriage will help direct you. After you have reached your destination, you will disembark and follow signs for the exit. To leave the station, there will be another ID check before you exit the station.

Conclusion

As a bespoke luxury tour operator, Imperial Tours will always defer to the wishes of its guests in selecting their preferred mode of transport. That said, whilst we previously assumed (non-private jet) guests would travel domestically by commercial carrier thanks to speed and overall convenience, there is now an option for a climate-friendlier alternative for many transits. Given its reduced cost, comfortable spaces, reliability, insight into the countryside and lower carbon emissions, travel by train for journeys of approximately four hours or less offers a compelling alternative.

Leading Beijing journalist, Andy McEwen, contemplates China’s global responsibilities from the dizzying heights of her futuristic technological platforms:

Google caused a big stir in China earlier this year when its artificial intelligence system beat the world’s best Weiqi (围棋) player at a tournament in the ancient canal town of Wuzhen, China. “The age of intelligence” is here, Google chairman Eric Schmidt announced to a previously quite naive world. This impressive victory for American knowhow created quite a stir in the West too, but for rather different reasons. “That’s great! Good for Google!” came the comments from western friends on social media. “By the way, what’s Weiqi?”

Tsk, tsk. You really need to take a refresher course on China. As every Beijing schoolboy knows, Weiqi invented in China 2,500 years ago, is the oldest board game continuously played today. Better known in the west under the Japanese name of “Go”, it is a two person game of strategy, the kind of intellectual activity ambitious Tiger Mums in Beijing sign up their kids to play on a Saturday morning when their peers in England are kicking a football around a pitch instead. About 300 times more complex than chess, this massively popular pastime involves the careful placement of black-and-white counters and, often, the pensive stroking of a wispy beard.

A group of young Chinese students playing Weiqi

Losing Grandmaster Ke Jie was reduced to tears. His digital opponent AlphaGo was “perfect, flawless, without any emotions,” the 19-year-old was quoted as saying in the New York Times? “Last year, it was still quite humanlike when it played. But this year, it became like a god.” AlphaGo demonstrated to us all that artificial intelligence, the idea that computer systems can perform functions typically associated with the human mind, is no longer futuristic speculation but present-day reality. For fans of zombie apocalypse movies, AlphaGo’s omnipotence poses troubling questions about the future of humanity. In a now-famous Open Letter on Artificial Intelligence of 2015, public intellectuals Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk et al warned “we could one day lose control of AI systems via the rise of super intelligences that do not act in accordance with human wishes – and that such powerful systems would threaten humanity.”

I, for one, welcome our new overlords: partly because they may be reading this, but also because I am old enough to recall life before the machines. I remember leaving a series of increasingly frantic messages for a friend with the receptionist of a rather haughty London hotel back in the noughties. No smartphone back then — only the trusty receptionist, who carefully transcribed all my messages and handed them to the wrong person in the next-door room. I remember, too, the reams of paperwork required to book a flight from London to Beijing via Paris. I remember faxing it all to somebody who faxed it again to somebody else, or something. Oh the fun we had photocopying passport pages and inking in ticket numbers! Oh yes I remember 2006, the year before the iPhone. It was a simpler time, only with more paper, lots and lots and lots of paper.

My colleagues in Beijing do not fret as I do about the prospect of the Terminator marching into the office, staple guns blazing. They welcome artificial intelligence as a means of replacing repetitive workplace drudgery with multiplying leisure opportunities in their pursuit of limitless personal fulfillment. Beijing is backing artificial intelligence with vast sums of money. Just like their western counterparts Amazon and Google, Chinese tech companies are embracing the enormous potential of AI from autonomous cars to facial recognition. When not too busy playing Weiqi, the Chinese are funding moonshot projects, exosuits for disabled people and robots to teach children computer science.

Take WeChat. Haven’t heard of WeChat? Where have you been? The West, presumably. WeChat is China’s most popular chat app, with over 889 million users as of the end of 2016. Fifty percent of users reportedly spend 90 minutes a day inside the app. And what is WeChat? That’s surprisingly difficult to answer. WeChat is basically Whatsapp plus Facebook plus er, the internet. In China, WeChat pays all our restaurant bills, orders movie tickets and unlocks rental bicycles. And more, much more.

WeChat, the super app, can essentially help you manage everything in one app

WeChat’s parent company Tencent launched a payments service in 2013 that now occupies 37 percent of China’s mobile payment industry. Wherever you shop in Beijing now you will see young people wafting phones at service people, ready to be scanned and presumably uploaded to the Matrix. WeChat even splits the bill equally among a group of buyers of, well, you know, stuff. WeChat is about the only thing from China that I ever successfully converted my family in London to adopting. They all prefer it to feebler western alternatives like FaceTime or Skype. Mum especially likes push-to-talk, a neglected feature in most western countries but a preferred method of chat over here. Now she can leave me reminders to call home. For free. Daily.

I wonder if Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has a WeChat account. He really should get one. It’s so much better than Messenger. Quicker than you can say “Skynet”, WeChat’s savvy boffins seem to sense what customers want and integrate the AI into all their products. “Basically, anything you need to do online can be done through WeChat,” Dr Andy Chun, a leading AI expert and associate professor at City University of Hong Kong told Quartz recently. “WeChat is much more ingrained into the average Chinese citizen’s daily life than Alibaba or Baidu (the Chinese search engine equivalent to Google). Amazon and Google do not have anything comparable.”

Dong Yu, former Microsoft employee, now new head of Tencent’s Seattle based AI labratory

On May 2, Tencent confirmed it was opening a laboratory in Seattle dedicated solely to artificial intelligence research to be headed by Yu Dong, a former scientist at Microsoft Research. “I have a hard time thinking of an industry we cannot transform with AI,” Andrew Ng, chief scientist at Baidu, told the Atlantic magazine. Ng previously cofounded Coursera and Google Brain, the company’s deep learning project. The implications of AI for a nation of 1.3 billion people and the world’s second-largest economy are mind-blowing, the dystopian alternatives rather too easily imaginable. Economists have suggested that automating workplaces with AI could add 0.8 to 1.4 percentage points to China’s annual GDP growth. But of course wider adoption of these technologies also presents a profound challenge to China as “the workshop of the world”, with the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of Chinese workers and Chinese society as a whole hanging on the right or wrong decision. With great technology comes great responsibility.

But what does it all mean? Well, either manmade robots will take over the world, or these technological feats will help bridge cultural diversities around the world. In the 21st century, I believe China will collaborate internationally in the development and governance of AI, ensuring that the necessary frameworks are in place to ensure that these breakthrough technologies make a positive contribution to global growth and human welfare. I have great faith that the world will get it right. Or to put it in Hollywood English, I believe if we all pull together as a team, unite as a planet, we can and will defeat our robot overlords.

The Retail Revolution

China has fast become the holy grail of shopping. Be it high-end or low-end, costly or counterfeit, China is the place where you can find just about everything. In the last decade, the biggest manufacturer in the world has developed the largest consumer base globally. This large population of freshly minted consumers has caused luxury retailers to scramble for a piece of the pie, or should we say, cookie? While sold out Louis Vuitton shops and limits on how many Rolex’s one customer is allowed to buy have been picked up by Western media, another retail revolution has prospered largely unnoticed within China’s borders; online shopping. With $900 billion in sales in 2016 alone, and responsible for almost 47% of digital retail sales worldwide, China has eclipsed the US and is now the largest online retail market in the world (Retail & Ecommerce, August 18, 2016). The story of how this rapid growth in retail evolved is almost fatalistic, with multiple companies taking advantage of an economic environment primed for shopping.

From Zero to Hero

In comparison to many Western countries, wealth and technology are relatively new to China. A significant portion of the Chinese population only began to experience a degree of economic prosperity in the mid 2000s. The rise of the middle class in China has been rapid. During this time of economic expansion, the number of households with an annual income of US$11,500 – US$43,000 grew from 5 million in 2000 to 225 million in 2016 (Economist, 2016). Along with this increase in wealth came an increased demand for technology. Instead of having to go through the technological steps Western consumers went through from gramophone to an iPhone, the first digital contact for many Chinese was either a smart phone or a tablet. However, since almost no digital or retail infrastructure had been built, and with no old infrastructure to tear down, Chinese companies who were able, were in the prime position to take advantage of this technological vacuum. From start-up delivery firms to creating new payment systems, this period laid the foundations for the new digital era.

Taobao – a populat online shopping site in China

Enter the Giants

The three largest online players in China presently are JD.com, Tmall aka Taobao (Alibaba) and WeChat. JD.com went online in 2004 and is the largest competitor to Alibaba-run Tmall, which was founded a year earlier in 2003. Both companies are B2C online retailers who have pretty much taken over China’s online retail market. While JD.com prides itself on having better quality controls on their brands and goods than their competitor, Tmall currently holds a larger portion of the overall market share and has deeper pockets financially. Alibaba, the parent company of Tmall became the largest global IPO ever when it went public in the United States in 2014. Combined, these two companies are the Chinese equivalents of Amazon and Ebay, the only difference being that their customer base is over one billion online savvy shoppers.

Enter WeChat, the super app. WeChat was first released in 2011 by its parent company Tencent, and with 850 million active users, it is now China’s most popular instant messaging application. While the logo and the name of the app look and sound similar to the American WhatsApp application, it is vastly different in its functions and capabilities. The best way to describe WeChat is a combination of Facebook, WhatsApp, Apple Pay, Instagram, TripAdvisor, SkipTheDishes, and online city services combined, but without the advertising. While this sounds quite chaotic and confusing, at its core WeChat is an instant messaging app with all other functions neatly hidden within. While WeChat is not an online retailer itself, it has created its own mobile payment system (WeChat Pay) and has a larger user base than Tmall or JD.com. However, recently WeChat has ventured into creating an online store, which soon could rival its competitors.

For these three companies China has become the digital ‘Wild East’ where opportunities abound. With more and more economic prosperity as well as a savvy online population, the e-commerce environment in China is the perfect breeding ground for digital entrepreneurs to thrive. Right now, between these three giants there is fierce competition for supremacy.

Online apps and sites It has become easier than ever to shop from anywhere

Shopping with Chinese Characteristics

In addition to a rich economic digital landscape, China’s unique political and economic landscape has resulted in oddities and strange paths to purchase.

One of these oddities is the phenomena of the Daigou, which literally translates to “buying on behalf”. Daigou’s are people living overseas who purchase luxury goods as well as items that can be hard to purchase in Mainland China like foreign baby-milk powder, and then sell them to customers living in China. These luxury items can be up to 30-40% more expensive in China and the Daigou either make a profit on charging a small fee for the service or claiming the tax refund. WeChat is the primary platform for Daigou to communicate with their clients as well as transfer money. Diagou is a huge business estimated to be worth around US$12 billion. Approximatley 80% of Chinese luxury purchases are made abroad and a survey of luxury shoppers has found that 35% of customers have used a Daigou to purchase goods online while only 7% used the brands’ website to do so.

Another oddity about Chinese people’s shopping culture is that there is very little trust in direct marketing and advertisement. This mentality has led to the rise of Key Opinion Leaders or KOLs. These are Chinese online influencers, similar to Bloggers or Vloggers in the West, who maintain trusting relationships with their often large fan base. This phenomenon has resulted in many companies hiring KOLs to endorse products or place ads in their feeds to market to their fans. Working as a KOL can be quite profitable if your fan base is large enough. For instance, KOL Papi Jiang, has a following of over 24 million fans on Weibo (China’s equivalent to Twitter) and was paid US$3.4 million for a single ad in 2016 (China Skinny 2016). While Papi has managed to amass her millions of fans through witty commentary and funny videos, other KOLs have made themselves experts on specific brands or items and often attend fashion shows to share their knowledge and expertise with their followers. One of these expert KOLs is ‘Mr. Bags’ a 24-year-old Beijinger with over 2.7 million followers on Weibo. Using his influence he claims to have helped brands sell over US$170,000 worth of designer bags in just 12 minutes (Business of Fashion, 2016).

Both Daigou’s and KOLs are phenomena that have emerged as a result of the unique position of the Chinese economy and its cultural past. While the world has opened up its markets to Chinese made products, not all foreign made products have found a way into the Chinese market yet, which has created a niche for the Daigou. Additionally, decades of state propoganda has made the Chinese population suspicious of anything written on billboards or aired on TV resulting in the rise of the KOLs.

Digital Destiny

In 2015 China’s e-commerce share of global sales were almost double that of the United States at 22.2% to 42.8% respectively. However, it is estimated that by 2020 China is on course to take up to 60% of worldwide e-commerce retail, while the United States share could drop as low as 17%. With an ever expanding middle class, with more disposable income, greater mobile and internet penetration into rural areas and growing competition of e-commerce players who are constantly improving logistics in China, infrastructure and payment systems, the environment for online retail is perfect. Additionally, one of the most astonishing aspects of this digital shopping revolution is that in 2016 more than half of all e-commerce transactions and sales in China were conducted on a mobile or tablet. Reading the signs on the retail horizon, it is a safe bet to predict that China’s shopping destiny is digital.

Now when traveling on an Imperial Tours Majestic Tour or an Ultimate China private tour, you will have free access to the internet outside the doors of your hotel. Imperial Tours’ China Hosts will be equipped with a mobile Wifi device so that guests will be able to surf the web and keep in touch with friends and family while traveling throughout the country. This means that while on a scenic drive through China’s idyllic countryside, you can email your friends and tell them what they are missing. Or, you can post on social media a photo of yourself enjoying a white linen banquet atop the Great Wall.

Travelers should also bear in mind that websites such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and from time to time Google and Gmail are inaccessible from China. Travelers who wish to use these sites during their travels in China should equip their devices with VPN software. Once installed, it is straightforward to connect with these websites.

If China’s Three Gorges Dam were as large as the controversy surrounding it, this would surely be the biggest dam in the world. Although it is the world’s largest in terms of electrictiy production and overall investment, it is not the biggest dam in the world. A close comparison in terms of size would be the Grand Coulee Dam in the U.S. which is slightly larger.

This is not to understate the impact the dam will have on China’s future development in terms of flood control, increased trade on the upper reaches of the Yangzi, and of course reduced energy prices.

The multiple aims of a massive Yangzi River dam have made this an enticing proposition for nearly a century. Sun Yat Sen, the founder of the Chinese Republic, supported the idea when it was first mooted in 1919. Chairman Mao, an avid poet, expressed his vision of the Three Gorges Dam in the following poem:

“Swimming” by Mao Zedong

“I have just drunk the waters of Changsha

And come to eat the fish of Wuchang.

Now I am swimming across the great Yangtze,

Looking afar to the open sky of Chu.

Let the wind blow and waves beat,

Better far than idly strolling in a courtyard.

Today I am at ease.

“It was by a stream that the Master said –

“Thus so things flow away!””

Sails move with the wind.

Tortoise and Snake are still.

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the north and south,

Turning a deep chasm into a thoroughfare;

Walls of stone will stand upstream to the west

To hold back Wushan’s clouds and rain

Till a smooth lake rises in the narrow gorges.

The mountain goddess if she is still there

Will marvel at a world so changed.”

In line 17, Chairman Mao makes clear reference to his ambitions for The Three Gorges Reservoir. It was his enthusiasm, along with that of Zhou Enlai, that precipitated the construction in the 1970s of the Gezhouba Dam on the Yangzi, the precursor to The Three Gorges Dam. It was Premier Li Peng however who, in 1990, forcefully pushed the Three Gorge Dam project back to center stage.

Conceived on an epic scale, but clouded in controversy, this will be one of the largest dams in the world for many decades to come. Here we introduce the fundamental statistics and themes of this mammoth project.

Three Gorges Dam Vital Statistics

| Dimensions: | 185 m (606 ft) high and 1,983 m (6,500 ft) broad | |

| Water Level Increase: | Water level is planned to rise in 2 stages; by 2004 it will increase by 30 m to 125m (426 ft) and by 2009 will increase another 50m to 175 m (575 ft) | |

| Cost Estimate: | 1985 Chinese estimate of US$10 Billion is acknowledged to be too low. Estimates abound from 2 to 5 times that amount | |

| Financing: | Mostly from a national energy tax; other portions have been raised from government bonds | |

| Materials Used: | 10.8 million tons of cement, 1.9 million tons of rolled steel and 1.6 million tons of timber | |

| Construction Period: | 1993 – 2009 | |

| Land submerged: | 13 cities, 140 towns, 1352 villages, 657 factories & 30,000 hectares of cultivated land | |

| Relocation of People: | 1.3 million to be relocated in 3 stages in 1997, 2003 & 2009 | |

| Energy Production: | 84 Billion kilowatt hours per year; enough to supply 11-15% of China’s energy. | |

At its heart lie three main benefits, none of which go entirely undisputed: flood control, energy production and improved navigation. Here we lay out the principle arguments either way.

Flood Control – the primary reason for this project is to contain flooding in the upper reaches of the Yangzi. Critics counter that this is only to the maximum height of the dam – 185 meters. After the 22.5 billion cubic meter flood control capacity is exceeded, there is nothing to prevent the overspill from invading the exposed lower valleys. According to this argument, were the freak floods of 1954 and 1870 to recur the dam could do little to contain them. Further, these critics argue, in terms of flood control this dam does nothing about the problem of flooding in the middle and lower reaches of the river.

A corollary to the flood control benefit of the three gorges dam project is the plan to construct a 600 kilometer canal from the three gorges reservoir to Beijing. From 2007, this will be able to divert up to 80 billion cubic meters of soft water per year to the water-starved north .

Energy Production – China’s phenomenal economic growth has killed the debate surrounding this issue. It now appears that the Chinese leadership was correct to assume the utility of the dam’s electricity production. Whereas naysayers had argued that China’s coal production would keep pace with her industrial development, this is certainly no longer the case. Already, in 2005, China is importing one third of its energy needs.

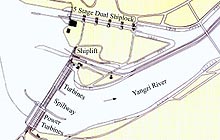

Navigation – the huge reservoir created by the dam will make the upper Yangzi navigable to 10,000 ton barges. To date the water levels of The Three Gorges have limited passage to 3,500 ton barges. Given the growth of Chongqing, China’s most populous municipality, proponents of the project claim that the Three Gorges Dam will reduce freight costs and facilitate trade in this area. Some scientists however, fear that the soil erosion caused by excessive tree felling in the Yangzi’s upper waters will result in large deposits of silt at the dam and along its backwaters to Chongqing port. This, they counter, will hamper navigation.

In considering the pros and cons of this ambitious, national project, it would be short-sighted not to acknowledge China’s expertise in the field. Between 1949 and 1980 China constructed 80,000 reservoirs and hydroelectric plants. One of these, the Gezhouba Dam, the first dam to be built on the Yangzi, was partly intended as a direct precursor to the Three Gorges Dam. As a result, the same construction company that built the Gezhouba dam, is also responsible for the completion of the Three Gorges Dam. Similarly, the excellent relations established between the Chinese government and Western companies like ABB, GE Canada, GEC Alstholm and Suzler Escher Wyss on the Geheyan Dam project will be put to good effect for the gigantic and spectacular Three Gorges Dam.