In the face of modernization, China is struggling to preserve its cultural heritage, and nowhere is this more visible than in the ancient hutongs of Beijing.

I have never been an admirer of the hutongs from an architectural or historical point of view, it was more about the buzz I felt as I meandered down these narrow alleys, seeing them bursting with activity. Sadly, the city’s rapid growth will no longer allow these vibrant communities to remain in these areas. The government’s continued efforts to modernize the city are incompatible with these dilapidated neighbourhoods but there is also a longing for change coming from within.

The word "Hutong" in Chinese means narrow street or alley. It refers to neighbourhoods within the old city walls which have existed since the 13th century. Typically these hutongs consist of rows of “Siheyuans”. These are rectangular single storey structures built in a square formation, which leave an open courtyard in the centre. In Imperial times these courtyard homes would have had a single owner, and different levels of decoration on their front door would indicate their economic and social status.

In modern china these courtyards are shared by many families, with one kitchen to be shared amongst them and the only toilet is the public one out in the street. What was once the home of a high-ranking official, is now home to four families who have lived together, generation after generation. There has always been a sense of kinship between these families and in the age of the single-child policy even more so; children see their neighbours’ children as siblings.

The hutong alleys are too narrow to be burdened by passing traffic and these neighbourhoods have become a labyrinth for pedestrians. I suggest one should only enter either accompanied by a local or riding a bicycle, as it makes finding your way out a lot quicker. Hutong residents have succumbed to the appeal of this open, traffic-less space on their door step and rather than spending their free time locked in their small confined dwellings, they choose to take whatever they are doing outside. When you wander through the hutongs, it is common to see kids playing badminton either side of an imaginary net, chess players bent over a board propped up on two bricks or someone squatting by a water basin doing their laundry. If you visit in the evening and start hearing 80’s dance music, you have more than likely walked into an open space where 80 pensioners are all dancing in synch to the music. A must see if you are visiting Beijing.

Unfortunately these areas in Beijing are slowly disappearing, making way for high rises, or they are rebuilt to be used commercially for tourists. Some more fortunate areas are restoring the courtyards to their former glory but their new wealthy landlords are less likely to take to the streets. Chess is played inside sitting on leather armchairs and all laundry is strictly washed behind closed doors. These sought after properties can be incredibly beautiful and valuable beyond the reach of most but their streets have lost all their communal charm and are now lifeless.

When the city decides to raze areas of hutongs, residents are given apartments in the city´s suburbs in exchange. Older residents prefer their humble homes to these distant, spacious modern apartments for fear that their lifestyles will be turned upside down. Younger generations are more aware of the comforts these newer homes offer and feel their allure. Beijing winter’s can be harsh and an indoor toilet and central heating alone will convince many. It is only a matter of time before broadband internet, a washing machine, air conditioning and a parking spot will get everybody else on board. Fortunately for me, this will not happen overnight and my Sunday afternoon walks to the hutong’s fruit and vegetable markets won’t come to an end any time soon.

This article by Imperial Tours’ founder about the tribes of Guizhou is for cultural informational purposes only. Imperial Tours does not offer services to these destinations as luxury faciltiies are not available.

By Guy Rubin

As cranes and bulldozers proliferate like ants across China, depositing cities and highways in their hammering trail, now is the time to venture inland in search of the more traditional side of China. In a vast crescent of land, curving from Guilin’s moonscape through the jungles of Xishuangbanna to the Tibetan plateau in the north west, reside many of China’s ethnic minorities. From the Dong to the Yi to the Bai, each minority, with its own distinct lifestyle, culture and mythology embodies a unique and refreshing vision of the world.

As cranes and bulldozers proliferate like ants across China, depositing cities and highways in their hammering trail, now is the time to venture inland in search of the more traditional side of China. In a vast crescent of land, curving from Guilin’s moonscape through the jungles of Xishuangbanna to the Tibetan plateau in the north west, reside many of China’s ethnic minorities. From the Dong to the Yi to the Bai, each minority, with its own distinct lifestyle, culture and mythology embodies a unique and refreshing vision of the world.

North-west of Guilin, Guizhou, a rarely visited, landlocked province is an anthropoligical treasure trove. Its poor farmland and geography, discouraging the interest of powerful neighbours, are home to 13 of China’s 60 officially recognized ethnic minorities. The tawdry provincial capital of Kaili, a five hour train ride east of Guiyang, provides a good base for explorations of the surrounding Miao villages.

Courtship, Miao style

On our arrival at Langde, south-west of Kaili, visitors were already being conducted into the village to participate in its New Year festival. At each turn in the zig-zagging path that climbed to the hillside village’s stone portal, children and beautifully bedecked local women were on hand to offer celadon-colored cups of the local wine. Their heads held rigid beneath ornate silver head-dresses, their bodies delicately poised in intricately embroidered, traditional costumes, they appeared like guardian angels at the gates of heaven. As I tipped one of the proffered ceramic cups back, glancing beyond its dark outer rim at the silver-framed, smiling child before me, I wondered how long this idyllic custom might continue.

On our arrival at Langde, south-west of Kaili, visitors were already being conducted into the village to participate in its New Year festival. At each turn in the zig-zagging path that climbed to the hillside village’s stone portal, children and beautifully bedecked local women were on hand to offer celadon-colored cups of the local wine. Their heads held rigid beneath ornate silver head-dresses, their bodies delicately poised in intricately embroidered, traditional costumes, they appeared like guardian angels at the gates of heaven. As I tipped one of the proffered ceramic cups back, glancing beyond its dark outer rim at the silver-framed, smiling child before me, I wondered how long this idyllic custom might continue.

My thoughts were interrupted by the warbling notes of lusheng pipes emanating from the stilted wooden homes. These hand-held, reed pipes, used by the Miao minority, have become the generic term for their courtship festivals. We hurried towards the music’s source; its wavering melody, enlivening the still, damp air, teased us through the village’s labyrinthine, stone-paved pathways. Skirting a moss-covered pond with a breath-taking view over the river, we eventually arrived at the main square.

Stepping onto the “Flower Ground”, also translated as the “choosing a lover ground”, we were overwhelmed by the bustling activity before us. This cobble-stone patterned courtyard, tucked in on three sides by beautiful, tiled houses and overlooking a low valley on the fourth, was a kaleidoscope of color and sound.

Dozens of elaborately clad girls and uniformed boys were crowding around each other. At a resolute, booming signal from a large bronze drum, the elderly folk, wearing dark robes with embroidered sleeves, guided their grand-children (ethnic minorities are exempt from the one child policy) to a nearby stone wall, clearing the square. They chattered amongst themselves as the boys, once more playing the lusheng pipes, led the girls through a delicate, shuffling dance of graceful bows and dainty hops.

Dozens of elaborately clad girls and uniformed boys were crowding around each other. At a resolute, booming signal from a large bronze drum, the elderly folk, wearing dark robes with embroidered sleeves, guided their grand-children (ethnic minorities are exempt from the one child policy) to a nearby stone wall, clearing the square. They chattered amongst themselves as the boys, once more playing the lusheng pipes, led the girls through a delicate, shuffling dance of graceful bows and dainty hops.

Although the mood is gay and the occasion light-hearted, there is little aimlessness about these courtship activities. Their goal is to bring together boys and girls of marriageable age for matchmaking. If a particular boy’s looks and dancing make some maiden’s heart palpitate and her knees go wobbly, tradition dictates that she should place a ribbon around his neck. If the boy is similarly smitten, he may show his interest by returning the talisman to her later in the day.

It appeared that the greatest risk to any ensuing relationship stemmed from the macho stunts the boys perform at the end of the festival to prove their mettle. Having walked across hot coals and lain on a bed of nails, one brave Miao youngster approached the tall pole in the center of the square. During the subsequent drum-roll, we noticed that the rungs punctured into this pole were actually comprised of up-turned, dagger blades – which the boy now circumspectly ascended. A villager informed us that the trick to doing this consists in not nudging your hands or feet sideways as you lay them on the blades. And if you do? In response, our interlocutor resignedly shrugged his shoulders.

As we were ambling out of this picture-book village, serenaded by the lilting tune of the pipes, we were loathe to acknowledge the undeniable influences of the modern world on this age-old festival. On a superficial level, many of the elaborate head dresses, used to differentiate women from various villages, were being replaced by a tacky assembly of bath towels held in check by plastic combs. More significantly perhaps, we observed a marked absence of young men in the crowd. A villager confirmed that many had left for the towns in search of work. The farms were barely surviving, he claimed, only kept going by the irregular remittances of these migrant workers.

An Inter-Village Bull-Fight

The very next day however, we drove by a terraced hill bedecked with such young men and their bulls. Leaping out of our minibus, we rushed past food stalls to see what was going on. It was an inter-village bull-fighting competition. And it was being conducted in deadly earnestness. While the men huddled excitedly around the bull-fighting ground, women and children sat disinterested, high on the hill.

Unlike their Spanish equivalent, these bullfights do not pit man against beast, but bull against bull. Having been drawn opposite each other, metal-tipped horn to metal-tipped horn, their oil-rubbed flanks glistening under the low, flat skies, it is a matter of seconds before the bulls’ heads lower and, with a crack, they aggressively ram each other. With their horns locked and their muzzles scraping along the kicked up turf, the bulls embark on a titanic struggle. Since each bull’s character is as varied as its physique, every fight, incorporating different fighting strategies, is absorbingly unique – the winner being decided in one of two ways. Either a team of judges selects a champion or else every so often one of the bulls flees, often into the nearby crowd, scattering exhilarated onlookers in all directions.

In the excited tension, articulated on every male face in the valley, there was no doubting the enduring fascination and enjoyment of this entertainment.

Ethnic Opera

More surprising perhaps, given the general disinterest of city dwellers, is the popularity of “dixi” or ground opera at a Bouyei village we visited. This local strain is derived from Han opera, brought to the region by soldiers from Nanjing during the Ming dynasty.

Glamorously dressed singers were surrounded by the whole village, who sat enraptured for the whole of the five hour performance. In fact, so enthusiastic was their reception, that the singers were called upon to repeat favorite arias for different sections of the crowd. For us, nonaficionados, it was as fun to watch the antics of the audience and chat with the villagers as it was to listen to the opera.

Guizhou’s relative poverty continues to shield its indigenous peoples from the encroachment of China’s predominantly coastal consumerism. Those travellers prepared to venture far from Guizhou’s main roads can still be rewarded with cultures who seem to have escaped the claws of time. As the incipient Chinese tourist industry gathers momentum however, expect the innocent spirit of these fragile societies to be compromised by the easy lure of the tourist dollar.

For more information, pick up a copy of “Guizhou, Southwest China’s Mountain Province,” by Gina Corrigan (Passport Books, ISBN I 0-8442-9896-4)

July 2000, Chinanow.com

Over the past two thousand years, perceptions of distance and scale have been continually exploded by technological advances. We now take for granted: airplanes, trains and roads; distribution systems that furnish ice-cool “Perrier” in the midst of a vast, baking desert. Yet even now, Nature with a flick of her skirt belies our pretensions to mastery. When you’re in the middle of a scorching desert, there is only so much your air-conditioning unit can do. Coaches turn back before an approaching sandstorm. Trains are only as reliable as their rail-tracks’ sandy foundations. And this is the twenty-first century. How much more treacherous would travel along the Silk Road have been two millennia ago? The monk, Faxian, traveling along it at the end of the fourth century, gives us an inkling:

“The only road-signs are the skeletons of the dead. Wherever they lie, there lies the road to India.”

Such were the perils of voyaging along one of the world’s oldest distribution systems. Like many good ideas, its roots lie in the military.

Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty decided in 138 B.C.E. to forge military alliances with kingdoms west of his northwestern archenemy the Xiongnu (or Hun) tribes. He charged General Zhang Qian with this mission, giving him one hundred of his best fighting men and valuable gifts to seal the military cabals. Thirteen years later, having been a Xiongnu hostage for ten years, General Zhang returned to the Imperial Han court with only one other member of the original party. Though he had failed to make a single military alliance, General Zhang enthralled the court with information of the thirty-six commercially vibrant kingdoms west of China’s frontier. Compounding the Emperor’s interest was his description of the magnificent horses he’d seen in the Ferghana valley (modern day Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan); horses that were stronger and faster than any in China, horses so fine as to render the Chinese army invincible.

Subsequent commercial and diplomatic ventures to the Ferghana valley failed to secure horses and so precipitated two full-scale Chinese invasions, the second of which in 102 B.C.E. succeeded in conquering all lands between China and the Ferghana Valley. The Chinese had secured not only horses but also foreign markets in which to sell their goods. Fifty or so years later, in 53 B.C.E., the Roman legions of Marcus Licinius Crassus on their doomed campaign in Parthia reported seeing wonderfully bright banners made of a marvelous, new textile.

In only a few decades all the ruling families of Rome were anxious to attire themselves in silk. By 14 C.E. this had gotten so out of hand that the Emperor Tiberius, disgusted by the revelatory bulges of this light and delicate fabric, forbade all men from wearing it. Before long the mystery of silk’s manufacture sucked Rome’s intellectuals into a blazing fervor. Pliny affirmed that “silk was obtained by removing the down from the leaves with the help of water.” Others countered that it grew like wool in the forest.

Its customers in a foment of wild curiosity, the prudent merchants of China made every effort to keep silk’s manufacture a secret. Sericulture was limited to the far off hinterlands of Sichuan, away from the prying eyes and the “big noses” of venturesome foreigners. Border guards, placed on high alert, double-checked all foreigners’ belongings.

Legion are the stories of silk smuggling. Some recount Persian monks disguising themselves as Christian missionaries, others describe English entrepreneurs stealing out of the country – with the wrong type of moth. The most romantic involves a young Chinese princess anxious to please her betrothed, the King of Yutian. When the King’s envoy revealed to her his master’s passion for silk, the princess resolved to smuggle the secret of silk to him.

A few days later the princess set off in a glittering cavalcade on her long journey westwards. Many days later, when they reached China’s border at Dunhuang’s Yumen Gate, her party was thoroughly inspected; even the princess’ personal belongings were closely scrutinized, much to the displeasure of the king’s envoy, Wei Chimu. After passing through the border gate, he approached the princess to inquire if she had succeeded in satiating his King’s love of silk. Removing her crown, the princess revealed silk worms hidden in her hair. Amongst her medicines, she showed him the mulberry seeds she had hidden in plain sight. Pointing at her serving maids, she revealed that, “all women in the Central Plains know how to grow mulberry seeds and rear silk worms.” Thus, it is said, did the secret of silk escape the confines of China.

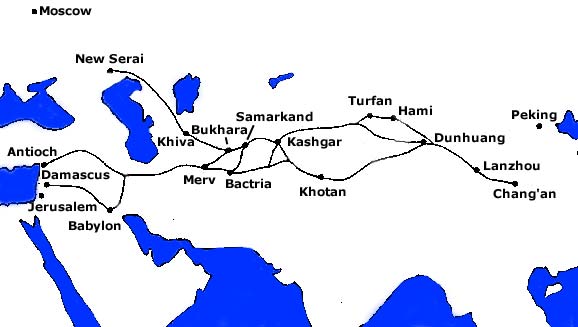

Though characterized in the 1870’s by the German geographer, Baron von Richthofen, as the “seidenstrasse” or Silk Road, it would be as inaccurate to suppose the Silk Road as a single trade route as it would to imagine that its only traded commodity was silk.

The Silk Road can be thought of as an East-West network of interconnecting routes linking various Central Asian Kingdoms such as those of Bukhara, Samarkand, Bishkek and Islamabad in the west with major China cities; most notably the Han and Tang dynasty capital, Changan (modern day Xi’an) in the east. The two major arteries of traffic skirted the northern and southern edges of the Tarim basin, which in the west is popularly referred to (along with other areas) as the Gobi Desert. Both northern and southern routes merged shortly before the Yumen Pass on the outskirts of Dunhuang, whence the traveler followed the Hexi Corridor southeast into the central plains of China.

It was not common for traders to traverse the entire length of the Silk Road. Customarily, traders distributed goods across their region’s markets in search of the best price. When the trader arrived at the edge of his operational region, he would sell the goods across a border usually to a different nationality and ethnic group who would continue the goods’ passage along the east-west axis. Thus, going westwards from China, Chinese traders would sell to Central Asians, who would deal with Persians, who connected with Syrians, who did commerce with Greeks and Jews, who supplied the Romans.

The greatest volume of goods were traded along the Silk Road during the Tang dynasty (618-907), particularly during the first half of this period. The Chinese predominantly imported gold, gems, ivory, glass, perfumes, dyes and textiles and they exported furs, ceramics, spices, jade, silk, bronze and lacquer objects and iron.

Of import for the world’s development were the inventions and ideas shared between east and west as the result of the increased trade and communication. Can we underestimate the impact that inventions like the plow, paper or movable type had on the development of the west? Similarly, China was immeasurably enriched by the introduction of Buddhism from India.

Buddhism is one of China’s three main religions, the other two being Daoism and Confucianism. Unlike the latter two however, Buddhism is not indigenous to China. It is a foreign import from northern India. As such it is representative of a strain in Chinese thinking that is receptive to accepting foreign ideas. (That said, some Buddhist doctrines were adapted in order to fit more successfully into the Chinese belief system.)

Within five centuries of the opening of the Silk Road to Central Asia, Buddhism had become so prevalent in China that some scholars estimate as many as 90% of her population to have been converted to Buddhism. By the Northern Wei dynasty (386-535) this religious philosophy had so penetrated the ruling elite as to inspire massive public works programs at some of the world’s finest cave complexes atMogao, Yungang and Longmen. And in 629, early in the Tang dynasty (618-907), concerns for textual authenticity inspired China’s most famous pilgrimage. The monk Xuanzang departed from Chang’an (modern day Xi’an) on a sixteen year journey to northern India in search of original Sanskrit texts. When he returned with over 600 such texts, the Wild Goose Pagoda was constructed in Chang’an (modern day Xi’an) as a library for these texts.

The first half of the Tang dynasty was the heyday of Chinese Buddhism. It enjoyed immense popular and imperial favor. China’s only Empress, Wu Ze Tian (625-705), in particular, sponsored many Buddhist projects, notably the massive White Buddha statue at the Mogao Caves. But in the end Buddhism became a victim of its own success. So widespread and complete was its displacement of traditional Chinese belief systems, such as Daoism and Confucianism, that in the second half of the Tang dynasty it provoked a series of conservative counter-reactions from which it never fully recovered. This demise occurred hand in hand with an increase in coastal sea trade, which came at the expense of the Silk Road. As a result, China’s focus was distracted from the devout Buddhist kingdoms of Central Asian which soon converted to Islam.

Though Western music is popular among China's younger generation, traditional Chinese music can often be heard in parks and back street tea-houses. There, to the delight of an enthusiastic audience, aficionados gather to sing their favorite operatic arias. Of China's various operatic schools, the most famous is that which developed in her capital city, referred to simply as Beijing opera.

Though Western music is popular among China's younger generation, traditional Chinese music can often be heard in parks and back street tea-houses. There, to the delight of an enthusiastic audience, aficionados gather to sing their favorite operatic arias. Of China's various operatic schools, the most famous is that which developed in her capital city, referred to simply as Beijing opera.

This grew from the comedic and balladic traditions of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), its current form taking shape some two hundred years ago. Emperor Qianlong (r. 1736-1796) of the Qing dynasty, on a tour of southern China, is said to have developed a passion for opera. For his eightieth birthday therefore, he invited opera troupes from all over the country to perform in the capital. So impressed was he with the troupes from Anhui and Hubei provinces that he insisted they remain to develop what we nowadays refer to as Beijing opera. The synthesis of styles is still evident with the clown, female and child roles singing in Beijing dialect and the male and more serious adult roles singing in Hubei and Anhui dialects.

Beijing opera incorporates not only song and dance, but also acrobatics, martial arts, colorful make-up, and elaborate costumes. The singing is accompanied by string, wood and percussive instruments, consisting mainly of gongs, drums and clappers. The principal drummer, serving as the conductor, directs each scene's prevailing mood. Since the stage is usually bare, the audience's attention is directed to the actors' gestures, each of which is invested with meaning. Walking in a circle, for example, indicates a long journey. Two men somersaulting under a spotlight indicates a moonlit flight.

Unlike Western opera, where roles are categorized by voice, this is done in Beijing opera according to the characters' gender, age, social status, rank and disposition. Make up plays an essential role in distinguishing characters and their moral qualities. Whereas a red face indicates bravery, uprightness and loyalty, a yellow one indicates brutality and a white one cunning. The clown, is distinguished by a small patch of white chalk on or around the nose.

Stories are derived from novels, dramas and historical epics, and are usually divided into civil and military subjects. The civil dramas, whose main characters are usually women, deal with such social themes as love, family, marriage and relationships while military dramas, whose characters are dominated by men, investigate themes of power and warfare. Generally speaking, the Chinese do not like sad endings, which may be one of the reasons why tragedies have never been popular. Comedy is always present with at least one clown to provide relief in even the most serious of stories.

cloisonné

snuff bottles

lacquerware

jade

seal carvings

silk

carpets

kites

After reviewing the craft subjects below, enjoy photos of crafts products in our Shopping Showroom .

Since 1904 when a Chinese cloisonné vessel won first prize at the Chicago World Fair, cloisonné has appealled greatly to foreign tastes. Developed during the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and perfected during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), cloisonné objects were originally made for use by members of the Imperial Palace.

The cloisonné process consists of casting bronze into various shapes to which copper wire is affixed in decorative patterns. Enamels of various colors are then applied to fill in the "cloisons" or hollows, after which the piece is fired three times. Finally, the piece is ground and polished to achieve a delicate luster and smooth surface. Today, cloisonné are manufactured in a variety of shapes and colors, ranging from such practical objects as vases, bowls, ashtrays and pens to such decorative objects as bracelets and animal figurines.

Snuff bottles were not indigenous to China, but were introduced from the West by the Italian Jesuit priest, Matteo Ricci, during the early seventeenth century. However, the art of painting the interior surfaces of the snuff bottles was a Chinese embellishment to this European craft. The story of how this tradition developed describes a Qing dynasty (1644-1911) official who, upon finding that his snuff bottle was empty, used a slender bamboo stick to scrape off whatever powder was left on the interior wall of the bottle. A monk, noticing that the bamboo stick left lines visible through the transparent wall of the bottle, came up with the idea of drawing entire paintings onto the interior surface.

Painted snuff bottles are mostly made of glass, although jade and crystal agate are used to make the most precious ones. These tiny objects, often no more than six to seven cm in height and four to five cm in width, are made by first forming a flat bottle and then filling it with iron sand so as to create a smooth, milky-white interior surface. After removing the excess sand, the minutely detailed painting is applied using a bamboo brush whose tip is bent. As the necks of the snuff bottles are often extremely narrow, painting the elaborate decorative schemes of flowers, birds and landscapes or of historical and legendary scenes requires both a great deal of patience and skill.

Remnants of lacquerware have been found in Zhou dynasty (11th century-476 BC) tombs, attesting to the long history of this craft. Lacquer is a natural substance obtained from the sap of the lacquer tree, a tree indigenous to China. Up to a few hundred layers of lacquer are applied to an object's surface in order to attain the final thickness of between five and eighteen mm. After the lacquer has dried, the object is decorated by carving various designs into the surface. While traditional imperial lacquerware came in the form of chairs, screens, tables and vases, today one can find objects ranging from trays, cups and vases to small decorative boxes.

The Chinese appreciation of jade dates as far back as the Shang and Zhou dynasties (16th century-476 BC) when jade carvings in the shape of discs or cylinders were placed inside tombs. Later, during the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), entire suits of jade were made to cover the body of the deceased. Jade is thought to possess magical and life-giving properties and was considered to be a protector against disease and evil spirits. It is also thought to symbolize characteristics of nobility, beauty and purity.

Today jade is used to create a variety of objects ranging from dishes and ashtrays to such decorative objects as jewelry, animal figurines or elaborate tree formations. While colors vary greatly, the most precious are those in shades of white, green, brown or those with variegated coloring. An ancient story which tells how King Zhao of Qin once offered fifteen towns in exchange for a famous piece of jade shows the value that the Chinese place on jade.

The earliest seal carvings date back some 3,700 years when oracle inscriptions were cut into the surfaces of tortoise shells. Considered with painting, calligraphy and poetry one of the "four arts" of the accomplished scholar, seal carving is an art that is unique to the Far East. Unlike the West where handwritten signatures suffice, in Asia, from imperial times to today, seals are used to officiate documents, show ownership or sign a work of painting or calligraphy.

Seals are made from a variety of materials such as stone, wood, metal and jade as well as in a wide range of shapes and sizes. The surfaces of the seal are either left bare or carved with calligraphy or pictures, with one end left to carve the name of the owner. These days carvers will select a Chinese name for the foreign visitor, adeptly carving the object for its new owner. When purchasing a seal, don't forget to buy the red ink paste used with the seals.

Although the exact date for the invention of silk is still debated, it is said that it was the Empress Xi Ling who started the tradition in the year 2,640 BC. Silk itself comes from the cocoon of the Bombyx mori, an insect indigenous to China. The threads of six or seven cocoons are needed to produce a single fiber strong enough to endure the subsequent weaving process. After weaving, the silk is sent to factories to be dyed or made into cloth, carpets or embroidery.

Today, the best silks are produced in Zhejiang province, particularly in Suzhou, as well as in Guangdong and Sichuan provinces. One can buy bolts of silk fabric in a variety of colors, designs and qualities or select from a wide selection of ready-made clothes of traditional or modern design.

Carpet-making came to China during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) when Tibetan lamas were summoned to the capital to produce carpets for the Imperial family. Carpets vary greatly from region to region, those made in Beijing employing such traditional designs as dragons and phoenixes, longevity characters, flowers, trees, cranes and scenes from classical Chinese paintings. Most carpets available for purchase in China hail from carpet-making centers in the autonomous regions of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet.

Kites were invented by the Chinese over two thousand years ago during the Warring States period (475-221 BC). The earliest kites, which were made of wood, were not made for recreational but for military purposes. Stories tell of soldiers tying themselves to kites in order to survey enemy positions. Alternatively, musicians attached bamboo strips to kites to create the vibrating sounds of a string instrument. Another interesting use of kites came about during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) when people thought that flying a kite and then letting it go would send off one's bad luck and illness.

Today kites are made in a variety of designs and materials. There are over three hundred designs including those of insects, fish, birds and written characters. The frame of the kite is always made of bamboo while the cover made either of paper or silk. The painting is generally done by printing the designs onto the paper, though some custom-made kites are hand-painted and may include such portentous designs as a pine tree and crane for longevity or bats and peaches for good luck.

The history of Chinese ceramics began some eight thousand years ago with the crafting of hand-molded earthenware vessels. Soon after, in the late neolithic period, the potter's wheel was invented facilitating the production of more uniform vessels. The sophistication of these early Chinese potters is best exemplified by the legion of terracotta warriors found in the tomb of Emperor Qin (r. 221-206 BC).

The history of Chinese ceramics began some eight thousand years ago with the crafting of hand-molded earthenware vessels. Soon after, in the late neolithic period, the potter's wheel was invented facilitating the production of more uniform vessels. The sophistication of these early Chinese potters is best exemplified by the legion of terracotta warriors found in the tomb of Emperor Qin (r. 221-206 BC).

Over the following centuries innumerable new ceramic technologies and styles were developed. One of the most famous is the three-colored ware of the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD), named after the bright yellow, green and white glazes which were applied to the earthenware body. They were made not only in such traditional forms as bowls and vases, but also in the more exotic guises of camels and Central Asian travelers, testifying to the cultural influence of the Silk Road. Another type of ware to gain the favor of the Tang court were the qingci, known in the West as celadons. These have a subtle bluish-green glaze and are characterized by their simple and elegant shapes. They were so popular that production continued at various kiln centers throughout China well into the succeeding dynasties, and were shipped as far as Egypt, Southeast Asia, Korea and Japan.

Blue and white porcelain was first produced under the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368 AD). Baked at an extremely high temperature, porcelain is characterized by the purity of its kaolin clay body. Potters of the subsequent Ming dynasty (1368-1644) perfected these blue and white wares so that they soon came to represent the virtuosity of the Chinese potter. Jingedezhen, in Jiangxi province, became the center of a porcelain industry that not only produced vast quantities of imperial wares, but also exported products as far afield as Turkey. While styles of decorative motif and vessel shape changed with the ascension to the throne of each new Ming emperor, the quality of Ming blue and whites are indisputably superior to that of any other time period.

During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), porcelain was enriched with the innovation of five-coloured wares. Applying a variety of under-glaze pigments to decorative schemes of flower, landscape and figurative scenes, these wares have gained greatest renown in the West. In almost every major European museum, you will find either a five-colored ware or a monochromatic ware (in blue, red, yellow or pink) from this period.

The quality of Chinese porcelain began to decline from the end of the Qing dynasty as political instability took its inevitable toll on the arts. However, the production of porcelain is being revived as Chinese culture gains greater recognition both at home and abroad. In addition to modern interpretations, numerous kiln centers have been established to reproduce the more traditional styles.

According to ancient lore, when a Chinese man named Cangjie learned the divine secret of writing, the spirits were so angry that millet rained from heaven.

According to ancient lore, when a Chinese man named Cangjie learned the divine secret of writing, the spirits were so angry that millet rained from heaven.

Perhaps this was because one of the first applications of the Chinese pictograph system was in the practice of divination. This long-standing association between pictographs and the occultforces of nature helps explain the historic and continuing importance the Chinese people attach to writing and to the art of calligraphy.

On a par with painting, the art of calligraphy has gone through a long evolution resulting in the development of various styles and schools. It is generally divided into five scripts: the seal script ( zhuanshu ), the official or clerical script ( lishu ), the regular script ( kaishu ), the grass script ( caoshu ) and the running script ( xingshu ).

Zhuanshu (seal script) is the most archaic, and can be seen on oracle bones (used for divination) dating back to the Shang and Zhou dynasties (14th century-476 BC). Because of its long, developmental history however, there was great regional variation in its characters. In the above illustration for example, there are 40 different versions of the same auspicious character, shou (longevity).

L ishu (official script) was developed during the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC) in an attempt to standardize writing throughout the empire. This script can be seen on many stone inscriptions of the period. Kaishu (regular script) of which the oldest extant example dates soon after to the Wei Kingdom (220-265 AD), simplified the lishu . Its characters are the closest to the modern form, being square and architectural in style.

On the basis of the kaishu (regular script), the caoshu (grass script) was developed to allow for a quicker, more fluid style of writing. The final style, or xingshu (running script), lies somewhere between the kaishu (regular) and caoshu (grass) scripts in that at times the strokes are controlled and regular and at other times free and flowing. These are the three scripts most frequently used in modern times – master calligraphers compare them to a person standing (kaishu ), walking (xingshu ) and running (caoshu ).

An individual's writing is considered sufficiantly crucial that children are trained from a young age to perfect their writing technique. It is thought that a person's character and refinement can be gleaned from her style, the finest scripts being infused with the writer's vital, creative energy. Thus, calligraphic strokes will often be described in such organic terms as the 'bone', 'flesh', 'muscle' and 'blood' or with reference to such natural forces as 'rolling waves', 'leaping dragon', 'playful butterfly' or 'dewdrop about to fall'.

History

History

The Naxi are one of China 's 56 recognized ethnicities, and although they have lived on the edge of the Chinese empire for centuries they have preserved many remarkable features of their culture. Some say the Naxi are descended from a group of people known in Chinese historical texts as the Qiang, whose homeland included parts of the Tibetan Plateau as well as the western areas of Sichuan and Yunnan . The situation is complicated as there is still a recognized Qiang ethnic minority in Sichuan . All this really goes to show is that the Chinese attempt to provide categorical definitions of who is and who is not a minority ethnicity, and where the lines between different ethnicities can be drawn, is a thankless and sometimes impossibly misleading task. In the early history of Naxi Lijiang, the area was pressed on all sides – to the south was the strong and aggressively expansionist non-Chinese state known as Nanzhao which was run by some combination of the Bai and Yi peoples; west of course lay the flourishing Tibetan empire at one of the strongest periods of its existence; while to the north-east were another group of Yi people, who also spent much of their spare time raiding their neighbors. While contacts with the Chinese proper have waxed and waned, the area only became formally integrated into the Chinese empire in the eighteenth century. For this reason perhaps there are a number of remarkable features of Naxi culture which have survived intact down to our day, they include language (especially the curious written forms), religious practices, music, and a reputation as being the sort of matriarchy that is somehow heaven for men.

The Naxi language belongs, appropriately enough considering that it is sandwiched between China and Tibet , to the Lolo-Burmese group. This group is a subset of a subset of the large Sino-Tibetan family which naturally includes Chinese and Tibetan. The Naxi also have their own written language comprising around 1500 pictographs. Like Chinese it is traditionally written top to bottom, but unlike Chinese it reads from left to right. It is not known when the writing first came into use but some estimates put it back at least a thousand years. It is not only, as one might surmise, limited to agricultural or trade uses – but has long been an integral part of the religious ceremonies conducted by the dongba, or local priests (and for this reason is known in Chinese as 'dongba writing' – although there is a newer modified form called 'geba writing' which is more a syllabary than a collection of pictographs, it also incorporates a Chinese influence).

Religion

Religion

Religion in the area is quite complex. As you would expect from a culture that borders so many others there is not a single faith or belief to the exclusion of others. Underneath many beliefs is an unsurprising animism, and then there are forms of Buddhism, of Taoism, of Tibetan Bon, and in recent times some Christianity. Most people are connected with what is called Dongba religion (once again named after the priests). The cultural anthropologist Emily Chao provides a succinct description of this and a related form of traditional Naxi religious activity:

The Naxi had two types of ritual practitioners who were often referred to as shamans: the dongba, often translated as "priest," and the sanba, translated as "shaman." Dongbas differed from sambas in that they acquired their skills through apprenticeships that required learning pictographic texts to be used in structured rituals. Dongbas usually inherited their professions and were always male. The role of sanba, open to both men and women, was not learned or chosen but resulted from a traumatic illness during which a channel communication with a spirit or god opened up. Aside from practicing purification and propitiation of the gods, sanbas do not follow standard or predictable sequences in their rituals. Neither the role of dongba nor that of sanba was prestigious, and it was often taken on by poor farmers seeking to supplement their livelihoods.

Traditionally shamans in the area wore cloth turbans, wielded swords or beat drums, and while doing so would chant their shamanic rituals in a whispered voice.

While the situation with religion is quite complex, it's the opposite with music.

Music

We defy you to find a Naxi person who does not enjoy singing or dancing. Since the 1980s traditional Naxi music has been increasingly recognised as an art form well worth cultivating and preserving. The comparative political relaxation of the 1980s made possible the resumption of minority cultural practices that had formerly been either frowned upon; discouraged as being backward and superstitious; or just outright banned. It was in this period that the famous Naxi orchestra initially began playing locally. Domestic and foreign tourists who came through in that decade were entranced, especially as the orchestra made a conscious effort to not 'modernise' their music, and the orchestra garnered a nation-wide reputation. This fame spread and in 1995 they undertook their first foreign concert tour, to critical acclaim. The orchestra comprises percussion, flutes, lutes, and pipes. While much of the music was borrowed from the Chinese several centuries ago the Naxi have made it their own, incorporating their own instruments and musical flourishes.

Matriarchy

Finally, a word about the sexes. Naxi men are well known for their laziness. Apparently, there are three ambitions for a Naxi man:

• Build a house

• Marry and have a son

• Bask in the sun

When they are not otherwise engaged, Naxi men enjoy hunting, raising birds, playing Naxi music and practicing calligraphy, a list that clearly shows a mix of traditional concerns (hunting) with Chinese influences (calligraphy, or pretensions to being a scholar). Naxi men use hawks in their hunting and previously they used to sit on the bridge parading their hunting hawks and watching the women walk by. Despite their much-vaunted reputation as a matriarchal society the truth is somewhat different. As a general rule young boys are allowed to be as naughty as they please, while girls help their mothers with the chores as soon as they are able. Furthermore, girls marry out, and kinship is reckoned from the father's side – making the whole social edifice appear a very male-friendly (if not wholly male-invented) form of matriarchy. The association of the Naxi with matriarchy seems to be an unfortunate consequence of another closely related ethnicity known in Chinese as the Mosuo, who do in fact practice matrilineal descent. The Musuo, who are based to the north-west of Lijiang, are classified by the Chinese authorities as belonging to the Naxi ethnicity, a categorization that the Naxi usually strenuously oppose.

One small piece of history – look for a missing index finger on the right hand of some elderly men. Apparently this indicates that they had no wish to be conscripted to fight for the Kuomintang against the Japanese in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The fight against the Japanese was another interesting chapter in the long-running story of a route which joined Lijiang with Tibet , a route which came to be known as the southern branch of the Tea and Horse Route .

Tea is one of ancient China's many inventions. The English word "tea" is derived from the word te, which hails from the southern port town of Xiamen (Amoy). Although it was only introduced to Europe and America in the seventeenth century, human cultivation of tea plants dates back two thousand years in China. In fact, during the Neo-Daoist revival of the ninth and tenth centuries, tea became an integral part of scholastic life. The preparation and drinking of tea symbolized man's potential for harmony with nature. The tea ceremony came to be a theater for spiritual enlightenment through the contemplation of the universe.

Tea is one of ancient China's many inventions. The English word "tea" is derived from the word te, which hails from the southern port town of Xiamen (Amoy). Although it was only introduced to Europe and America in the seventeenth century, human cultivation of tea plants dates back two thousand years in China. In fact, during the Neo-Daoist revival of the ninth and tenth centuries, tea became an integral part of scholastic life. The preparation and drinking of tea symbolized man's potential for harmony with nature. The tea ceremony came to be a theater for spiritual enlightenment through the contemplation of the universe.

This article lists the various categories of tea available in China and describes the process for making Hangzhou's famous Longjing tea. For more information, join us on a tour of Hangzhou's tea museum.

The Various Categories of Tea

1) Green tea . So called, since the green tea leaves are not fermented during processing, thereby maintaining the original colour. Famous examples are Longjing tea of Zhejiang province, Maofeng of Huangshan Mountain in Anhui province and Biluochun produced in Jiangsu province.

2) Black tea . Developed after green tea, it incorporates fermentation within the baking process. The best brands are Qihong of Anhui province, Dianhong of Yunnan, Suhong of Jiangsu, Chuanghong of Sichuan and Huhong of Hunan.

3) Wulong tea . This represents a variety half way between green and black teas. It is a special tea made and enjoyed in Fujian, Guangdong and Taiwan – all located on China's south-east coast.

4) Compressed tea . Also known as "brick tea" because it is compressed and hardened into a brick-like shape, this tea is convenient for transportation and storage. It is often supplied to nomadic peoples on China's borders, e.g. to clans in Mongolia.

5) Scented tea . This is made by mixing fragrant flowers with the tea leaves during processing. The flowers most commonly used for this are jasmine and chrysanthemum.

To Make Green Tea

To make Longjing (Dragon Well) Tea, bushes must be picked between twenty to thirty times between March and October. This is not done by machine but by hand, with an experienced leaf-picker able to collect six hundred grams or nine thousand green tea leaves per day. For all but the very finest tea, these fresh leaves are immediately parched by machine in electrically heated cauldrons.

Six hundred grams of fresh green leaves (or one day's worth of picking), after baking, will leave you with one hundred fifty grams of parched tea.

"They were the oddest hills in the world, and the most Chinese, because these are the hills that are depicted in every Chinese scroll. It is almost a sacred landscape – it is certainly an emblematic one."

"They were the oddest hills in the world, and the most Chinese, because these are the hills that are depicted in every Chinese scroll. It is almost a sacred landscape – it is certainly an emblematic one."

Paul Theroux, Riding the Iron Rooster, 1988

When looking at a Chinese painting, most visitors will remark upon the enormous differences from Western painting tradition. Foremost among the differences are the use of ink and silk paper as opposed to oil and canvas, the use of a silk scroll rather than a wood or metal frame as well as the general lack of verisimilitude to the original subject. Unlike most Western painting traditions, Chinese painting did not place great importance on depicting an exact likeness or replica of that which exists in reality, but instead emphasized the need to capture the spiritual essence of the subject. Whether it be a portrait in which the eyes were thought to reveal the true character of the sitter or a landscape in which the fluttering of leaves were thought to capture the hidden truths of nature, it was the rendering of the life force of the painting that was the ultimate goal of the painter

Such ideas are revealed in the first theory on painting which was written in the fifth century by Hsieh Ho. Entitled the "Six Elements of Painting" they advocate that the painting:

1) Have a life of its own, be vibrant and resonant

2) Have good brushwork that gives it a sound structure

3) Bear some likeness to the nature of the subject

4) Have hues that answer the need of the situation

5) Have a well thought out composition

6) Inherit the best of tradition though learning from it

While very few paintings from this early period exist, from the Sui (589-618 AD) and Tang (618-907 AD) dynasties onwards, painting came to assume its predominant position in China's artistic tradition. Especially popular were portraits and scenes of the Emperor's life with envoys or court ladies, as well as scenes of nobles' lives found on tomb frescoes or Buddhist imagery found on grotto walls. Some of the greatest treasures of Chinese painting are the frescoes found on the walls of the 468 Buddhist grottoes in Dunhuang in Gansu province. For more than ten centuries, artists painted scenes from Buddhist sutras as well as portraits and scenes of the lives of the numerous people who traveled along the Silk Road.

During the Song dynasty (960-1279 AD), a painting academy under imperial patronage was established, with two main styles of painting coming into emergence. The first style, known as academic painting, favoured bird and flower paintings depicted in minute detail. The second style, known as scholarly painting, favoured grandiose landscapes. Unlike Western landscapes which emphasized perspective and shading elements, Chinese landscapes stressed the brush stroke which could be variegated in thickness and tone. Also diverging from Western styles was the unimportance of man as figures were kept to a minimum and always depicted much smaller than the background landscape.

In the succeeding Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), a literati school comprised of scholar-painters, came into emergence. Painting was always considered the domain of the educated elite and at no other time was this ideal more apparent. The most widely painted subjects were the so-called four virtues of bamboo (a symbol of uprightness, humility and unbending loyalty), plum (a symbol of purity and endurance), chrysanthemum (a symbol of vitality) and orchid (a symbol of purity) as well as bird and flower paintings.

The Ming dynasty (1368-1644) favoured a return to tradition as artists copied the masterpieces of early times. In fact, painting manuals were written which contained prototypes of a certain leaf, rock or flower which the artist could then copy and combine to create a new work. Unlike the West which always emphasized individuality and creativity, both in painting and literature, the Chinese greatly appreciated the need to master tradition before undertaking the new.

While traditional styles continued to dominate the work of painters of the subsequent Qing dynasty (1644-1911), increasing contact with the West brought about the inevitable influence of Western styles. The Italian painter, Guiseppe Castiglione once even worked under imperial patronage, thus introducing to his Chinese contemporaries such Western techniques as shading and perspective.